Brief

Most leaders have an intuitive sense of the importance of behavior in business performance. They know from experience that it all comes down to not only what their people do or don't do but—just as importantly—what's expected of them and what corporate habits motivate their actions. Typically, leaders learn from trial and error that some of their people's behaviors produce superior business results and others don't. They also learn that their own behaviors have an enormous effect on their organizations' performance. They begin to realize that ingrained behaviors become corporate destiny. But does this process have to be hit or miss? Can firms systematically and rigorously develop and manage behavior to achieve predictable and superior performance?

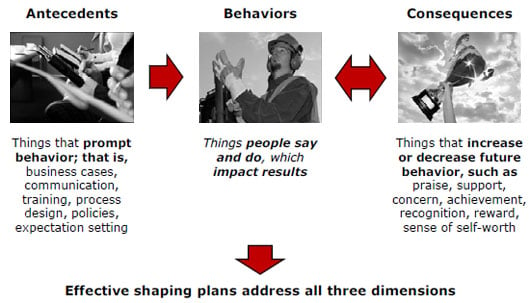

The short answer is yes, and the field of applied behavioral science (ABS) reveals how. ABS offers compelling insights into what actually influences human behavior. It shows that any behavior—what people say or do—is prompted by antecedents and then powerfully reinforced or undercut by the consequences of those actions.

Antecedents might include a client request, manager expectations, training, policy, communication or even an unpredictable impulse.

Consequences come in such forms as feedback, support, concern, correction, disillusionment, results or rewards. These latter are all-important in setting durable patterns. Indeed, depending on whether they are perceived to be positive or negative, the behavior will be increased, maintained or decreased in the future.

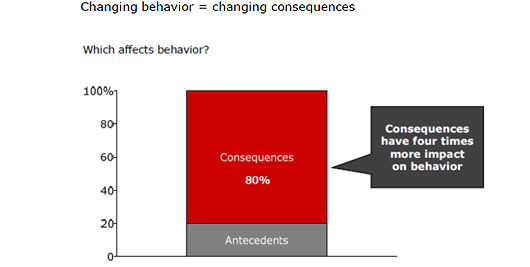

In fact, studies show that consequences have about four times more direct effect on behavior than antecedents. Yet most organizations place four times more emphasis on antecedents than on consequences. For example, we have all heard the phrase, "Walk the talk." We know it to mean that people expect leaders to do what they are telling their employees to do.

Now, let's look at this principle from a behavioral standpoint. A leading consumer goods company routinely sends hundreds of high-potential managers to training classes for leadership skills. There, the company drills highly ethical principles as antecedents into them. The managers return to the office energized and enthused about putting their new skills into action. But then they observe that a supervisor or a senior leader who uses an entirely different leadership style receives a promotion. The inevitable, unintended consequence: these brand-new leaders are almost certain to behave in a way that is the opposite of what they were just taught.

The "talk" becomes just that, while the consequences can become devastating to long-term corporate health. Here's how: When rhetoric is not backed up by behavior, people learn to ignore leadership directives. Worse, leaders appear to lack control, and the organization loses confidence in its leadership.

Catching people winning

Positive consequences, on the other hand, are extremely motivating and can come from a variety of sources: organizational incentives and promotions; supervisors' feedback, praise and thanks; peer recognition and group acknowledgment; and even the self-satisfaction of meeting one's own goals and standards or from hitting process-performance targets or sales quotas.

How motivating are these positive forces? As we noted earlier, consequences that are encouraging and reinforcing have about four times more impact on motivating desirable behaviors than discouraging ones, research has found. Maximizing this positive effect depends on how closely organizations match good behavior with good consequences. Three factors are key.

- Direction: Does the consequence affect the performer positively or negatively?

- Timing: Does the performer experience it immediately after the behavior, or is it delayed?

- Likelihood: From the performer's perspective, is the consequence likely or unlikely to occur?

The most effective consequences are positive, immediate and likely (PILs).

A systematic approach to changing behaviors

One of the key insights emerging from behavioral science is an understanding that the way in which your people conduct their everyday actions at work is just as vital to achieving a company's targeted results as its processes. In fact, they are as linked as a bow and arrow. To hit the target, behaviors thus have to be aligned tightly with strategy and rigorously managed to achieve performance goals.

Again, however, relatively few organizations make a consistent effort to lead and manage for the behaviors they need. Successful ones that do so begin by identifying the critical few behaviors needed to reach their strategic and operating objectives. They then thoroughly prepare and equip leaders at all levels to deliver those essential behaviors, the ones that make things happen.

They understand that the thoughtful application of ABS principles provides an effective road map for reliably creating the kind of "good behavior" that is self-reinforcing. This pathway focuses on the following actions:

- Pinpoint the few critical behaviors that most affect results;

- Identify who performs them;

- Develop a step-by-step plan to shape new behaviors;

- Devise ways to measure both the behaviors and successful results and;

- Sustain the results through positive reinforcement.

Let's examine each in turn.

Pinpoint the critical few behaviors that most affect results

The most successful organizations carefully identify the small number of behaviors that have the most direct impact on the specific business results they aim to achieve. For example, if a desired change involves revamping the organization's decision style from consensus to participative management, anticipated behavioral shifts might include these steps:

- Involve the right people in the decision-making process (according to their qualifications and the amount of flexibility the situation allows).

- Listen carefully to and consider the ideas of others by practicing attentive listening and note taking.

- Demonstrate others' acceptance of new ideas by repeating their input.

- Explain the rationale behind the decision to those who offered input.

- Use consequences to reinforce positively those who support the decision and provide corrective feedback to those who do not.

The key is to focus on only the critical few behaviors for any situation. Attempting to change too many at once, even if they are desirable, is not effective. When Jim Kilts was at the helm of Gillette, he initially focused on changing just one behavior: he made sure that his team behaved in a way that was always supportive of decisions. Previously, the corporate habit had been to indulge in subversive hallway chatter. That was characterized by minimal discussion in a meeting, but passive resistance outside. To change this harmful behavior, Kilts and his team agreed to have open and honest debate during the discussion but then would stick by and support a decision once it was made.

Identify who performs them

To change ineffective behaviors, companies also need to reinforce the desired new corporate traits by making sure that they are consistently displayed by the people who matter the most. In decision making, for example, the clandestine undermining of agreements not only has to stop, it has to be replaced by wholly new and open behavioral traits. Fortunately, there are proven methods to do this reliably. In the case of promoting a participative-management style, the population of key influencers is easy to identify when using a tool such as Bain & Company's RAPID®. (See "Who Has the 'D'? How Clear Decision Roles Enhance Organizational Performance," by Paul Rogers and Marcia Blenko, Harvard Business Review, January 2006.) Briefly put, RAPID posits that those involved in the decisions that most affect business value comprise a tight circle. They include the decision maker (the "D") or any of the other decision roles, such as those who recommend ("R"), provide essential input ("I"), must agree ("A") to go forward or ultimately perform ("P") the requirements of the decision. These, then, are the critical target population to focus on when shifting behaviors related to how a company makes decisions.

Develop a step-by-step plan to shape new behaviors

Often the gap between the current and a desired behavior yawns widely. Successful organizations undergird their people's journey to new habits by identifying challenging but achievable intermediate steps, the intent being to shape their behavior progressively. These companies also prepare and equip leaders at all levels to deliver those behaviors, and they ensure that leaders know how to manage consequences and reinforce key performers.

In most cases, this can't come all at once. For instance, when moving to a participative management style, a person formerly assigned delegation authority will need to learn how to step up and actually make decisions—a difficult task for someone accustomed to relying on consensus. Conversely, those who don't have the ultimate decision authority will need to learn how to support the decision, regardless of whether they agree or not. People who are no longer tasked with making a decision also need to refrain from getting involved and, instead, trust others to do a good job. None of these behavioral changes is easy or natural, though.

When MetLife was undergoing this kind of change, Bill Mullaney, then president of the company's institutional business unit, advised his leadership team to "get comfortable with being uncomfortable" at not being part of every decision. That was a simple first step, but it helped the team move toward its ultimate goal of becoming more adept at decision making.

Devise ways to measure both the behaviors and successful results

In our experience, effectively changing ingrained behaviors is actually one of the best leading indicators of the eventual success of change-management efforts. How do you know if it's working? Several monitoring tools let you set metrics and then track progress. At Gillette, CEO Kilts enforced the new behavior code through evaluation and rewards. Henceforth, he decreed, every year each executive would receive four job performance ratings based on their behaviors-one from themselves, one from their peers, one from their direct reports and one from Kilts himself.

At a bank we worked with, managers began continually to observe and track whether tellers offered new products to targeted customers. They tallied the cross-selling performance by teller, branch and region. Again, making such behavioral change stick wasn't a snap. It took persistence, abundant encouragement and immediate positive reinforcement in the face of a lot of rejection, since the likelihood of customer acceptance was only one in seven. Yet with platform managers working closely and understandingly with frontline tellers, the financial institution eventually did realize its cross-selling goals.

Sustain the results through positive reinforcement

As the bank example shows, the organizations most adept at changing behaviors understand that old habits are hard to break and need time to be replaced with better ones. They therefore provide their people with the tools, skills, resiliency training and motivation to deepen their "habit strength" and thereby sustain strategic results over time. Positive consequences for good behavior are embedded within the organization's business systems and its DNA. At Gillette, the behavior score affected a major portion of the executives' bonus pay. Not surprisingly, behaviors at the company soon improved, as did overall returns.

Any change aimed at improving performance cannot happen until individuals' behavior changes. When people's behavior is left to chance, results are unpredictable. Change must occur. The third dictionary definition for "change" is "substitute." To develop the kind of human conduct that will differentiate a company, leaders must replace trial and error with an action plan when it comes to behavior. Behavior patterns must be governed by the five critical rules of pinpointing the few critical behaviors that most affect results, identifying who performs them, developing a staged plan to shape new behaviors, devising ways to measure behaviors and results and, finally, ensuring a virtuous cycle through positive reinforcement.

The rewards will be well worth the effort. When the right behaviors become habitual, when they are consistently modeled by leaders, and when they are reinforced by policies and adopted by all, they create the kind of human willingness to perform great things.

RAPID® is a registered trademark of Bain & Company, Inc.