Founder's Mentality Blog

The core topic of workshops we ran with founder-led companies in Mumbai last week was “How to maintain the insurgency.” As we’ve been discussing in these blog posts recently, few management challenges are more difficult.

Most companies start as insurgents. They enter their market on behalf of an under-served customer segment and largely ignore the “rules of the game” defined by the larger industry incumbents. They are open to radical innovation in product and business model, doing whatever it takes to serve the target customer. They care little about the establishment and are united from top to bottom around a nobler mission. The goal of providing something new and truly different lends everything they do more meaning.

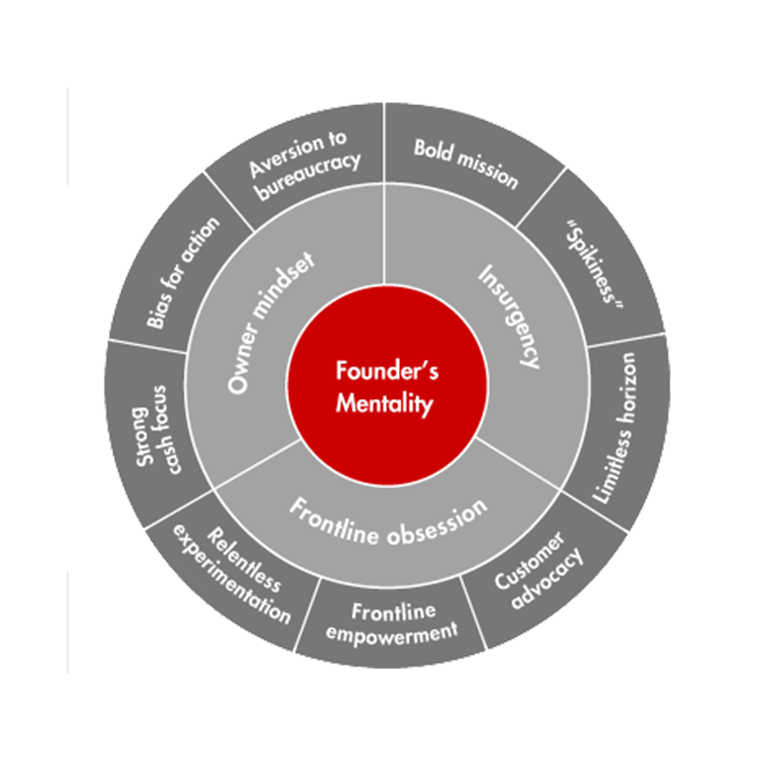

About the Founder's Mentality

The three elements of the Founder's Mentality help companies sustain performance while avoiding the inevitable crises of growth.

The great threat to insurgency, however, is success. As a company grows it slowly evolves into an established industry player. It may achieve stability and “incumbent economics,” but it loses the instinct to attack and innovate. Often without knowing it, management begins to spend more time defending the status quo than inventing new ways to serve the customer. For many, the real question is, “How do you revive the insurgency once it begins to fade?”

The acid test we often use in meetings with CEO and founders is this: If you think back to what you were like X years ago when you started this company, and knowing what you know now about your strategy, would you join your own company? Too often, this leads to a serious pause as leaders think about whether some of the initial magic has been lost.

The next test is whether leadership can restate the company’s strategy in a single sentence that sets out the under-served customer segment and the new or unique proposition that the company offers to help that customer. In our discussions with founders, notwithstanding their initial confidence that this should be easy, we’ve found it is really hard to get this sentence right. We’ve seen three major ‘traps’:

- Leaders start with the current strategy—their sentences are filled with financial targets or specific decisions about where they will or won’t invest. The statement becomes something like: “We will focus on the automobile sector, targeting 8% growth domestically and 16% internationally.”

- The leaders list out the capabilities required to win in their industry, developing a sentence that could be used by any of their competitors: “We will be the best innovator and most reliable partner.”

- The leaders define today’s current business model and set of assets, developing sentences that constrain their scope and ambition: “We will be the best supplier of low-cost healthcare solutions in Southern India.”

These traps radically narrow the original insurgent mission. They pull the leadership team toward an incumbency mindset by describing the world as it is and how the company will allocate resources to manage efficiently in this world. These traps lead to sentences that bore your socks off. They are visions that could have been spoken by any team on any day. They describe a generic company hoping to perform above average in an average world.

The goal of our Founder’s Mentality workshops has been to force leaders to investigate the original insurgent mission and to rediscover how radical and game changing it really was. This is an uncomfortable ride for some, because they arrive at the workshop quite confident they know their company well and can articulate perfectly its mission, strategy and operating plan in a sentence, a paragraph or even a 200-page book. Forcing these leaders to rediscover the revolutionaries within themselves is hard, but thrilling. And it produces great rewards.

Before giving a few examples, let me raise a caveat: When we talk about the original insurgent mission or the original core proposition, we fully recognize that this was not the founder’s initial idea on Day One. The core proposition that allows start-ups to grow from aspirational insurgents to major players takes years to develop and is the product of multiple team members experimenting with lots of ideas.

An analogy might be helpful here. In his classic book on evolution, The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins makes an interesting point about our solar system. Essentially, he notes that the planets that surround our sun (or any sun in any solar system) are the lucky lumps of mass following the big bang that just happened to fall into the sun’s orbit. If they had been too close, they eventually would have been sucked into the sun and burned. Too far and they would never have been caught in the sun’s gravitational pull. So the planets we see today are the lucky survivors—the few rocks out of gazillions that settled into a survivable, consistent orbit.

In the same way, the insurgent mission we are talking about typically formed over years of experimentation as discreet lumps assumed their orbit around the company in the center. From today’s viewpoint, Dawkins notes, it looks like our solar system was perfectly designed while in truth it was the product of chaos and radical movements. The same applies to great companies—their past was a lot more chaotic and radical then they remember.

That’s the key insight. The rediscovery of the insurgent mission is often a rediscovery of how expansive, innovative and radical the company’s original mission was. But for many leaders, this spirit of insurgency is exceptionally hard to recapture. Consider the example of one CEO in Mumbai. His initial sentence (and I’m disguising here) was “We will be the most trusted supplier of fairly priced electrical supplies to white goods manufacturers.” The group challenged him, saying that sounded too narrow and could be the statement of any company in that industry. He refined further, “We will be a fast follower on innovation in order to be a great partner for white goods manufacturers trying to serve the Indian market.’” Again, the group challenged, feeling he was listing generic capabilities. Soon, the discussion moved to someone else.

Then a little later, this CEO came back with something better: “At our best, we are ruthlessly local, promising the fastest time to market for local Indian white goods manufacturers trying to adapt quickly to the evolving needs of local Indian consumers.” The group stared at him. For the first time, he had mentioned two essential words—local and speed—that weren’t part of the earlier, lukewarm drafts.

Another CEO then asked him, “Does local and speed matter today?”

“More than ever,” he answered. “And as I reflect, almost every action we have taken to improve operations in the last three years has slowed us down, and eroded our ability to offer local solutions.”

There it was. The original insurgent mission was radical and unique. It was still highly relevant today. And most of his current initiatives were beginning to erode his ability to continue that mission, opening the company up to the threat of new incumbents. This happened again and again over the week. A CEO/founder would rediscover the insurgent mission, confirm it was still highly relevant today and reflect thoughtfully that many of the company’s recent initiatives were eroding its capacity to accomplish it.

The group had an “aha moment” when CK Ranganathan, the chairman and managing director of India’s CavinKare, told his story. It is a classic and often-used case study of innovation, so I won’t repeat it in detail here. What is important for this blog is that CavinKare was a radical rule-breaker in consumer goods, having invented the concept of using low-cost, single-use “shampoo sachets” to give the poorest Indian consumer access to shampoos. Its success redefined consumer marketing in India.

“We had a very clear mission that defined who we were,” CK noted. “’Whatever a rich man enjoys, the common man should be able to afford.’ This was extraordinarily aspirational for our team. The sachet was the first real innovation that allowed us to do this and drove our growth. And, of course, that led us to have shampoos strategies and hair-care strategies and think about price ladders and classic ways to compete in the space. But that wasn’t who we were—we had to learn the game and skills of FMCG companies, but we didn’t have to play by their rules or even always play their game. In fact, over the years, returning to this original insurgent mission has led to new innovations across categories. We are introducing radically new packaging for juices that allows for ambient temperature storage and new price points. This is a completely different category and a radically new packaging solution, but it is part of the mission.”

We’ve noted that the greatest successes among start-ups begin with a founder’s insight that recognizes an under-served consumer segment and how the company can uniquely support it. The rediscovery and reconfirmation of that mission is often the best way to maintain the insurgency. It reminds you how radical and innovative you originally were. It reminds you how unique you were and, more often than not, it opens up new opportunities for growth rather than shutting them down. Maintaining the insurgency is the best way to capture the discretionary energy of your people. It’s the best way to maintain the nobler mission.