Founder's Mentality Blog

Why do large industry players find it so hard to lead innovation or respond to fundamental disruption in their industry? As we emphasized in our recent discussion of “future makers” vs. “future takers,” it has a lot to do with subtle changes in mindset that build up over time. We’ll continue to examine the problem here by looking at the “innovation funnel”—the process by which companies generate and screen new ideas.

But first, a reality check: Despite the conventional wisdom that company size and innovation are somehow incompatible, the truth is that many large incumbents do an extraordinary job of leading innovation in their industry for long periods of time. Sadly, though, they are ultimately judged on the final test—the moment when they fail to take the lead on industry disruption and lose precious ground to one or more insurgents.

What happens? In essence, the change is a switch from an insurgent to an incumbent mindset—from future maker to future taker. Industry leaders cross a threshold and start viewing the future as a bad thing, instead of an opportunity. A look at how companies manage the innovation funnel demonstrates how this shift in mindset triggers a hundred subtle changes that turn the company inward and leave it on the defensive. The knights return from the edges of the kingdom to defend the castle walls. Their focus switches from searching for the lands of tomorrow to conserving the gains of yesterday.

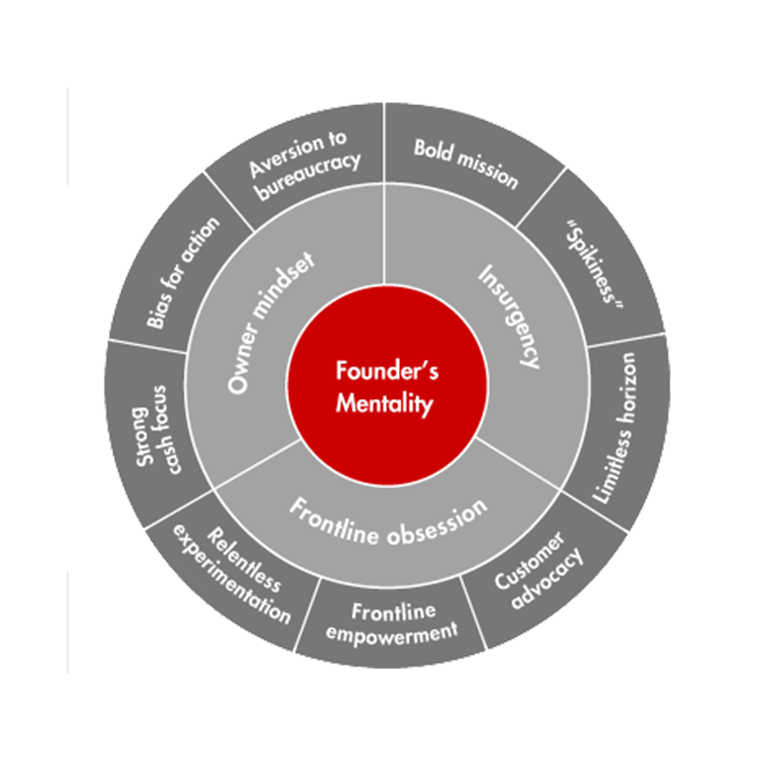

About the Founder's Mentality

The three elements of the Founder's Mentality help companies sustain performance while avoiding the inevitable crises of growth.

Another note: I know that I’m “cartooning” here—I’m comparing the ideal insurgent with the tarnished incumbent, which isn’t fair. And I’m broad-brushing everyone to explain failures. But I’ve explored these ideas with enough incumbent leaders to know that most of the arrows I’m firing here land—and most of them hurt. With that in mind, here are three aspects of how insurgents and incumbents manage idea generation, screening and scaling that highlight their differences in approach.

Idea generation. Simply put, the danger for incumbents is that they see all new ideas as “mice nuts”—that is, too small to worry about. While insurgents evaluate ideas based on how big they can be and how they might capture future trends, incumbents tend to measure them based on how big they are now and how they stack up to the company’s overall performance. A series of what we like to call “tyrannies” kick in to discourage incumbents from assigning new ideas more value. Let me highlight a few:

- The tyranny of the forgotten insurgency. For the most part, incumbents have mastered their industry. They control a good share of the profit pool, they excel at the industry’s “rules of the game” and they’ve successfully recruited talent to play on today’s fields. But they’ve often forgotten how innovative and disruptive the company was in its early days, which makes them less than enthusiastic about embracing new ideas that might distract from the core. That leaves them flat-footed when insurgents begin to attack from innovative new angles. I was talking to an industry leader this month who lamented: “We were founded on the notion of lowest costs and were amazingly innovative in our zeal to deliver low costs to our customers. Today, we face industry disruption from the Internet. The Internet should be seen as a great thing for our people: It enables our mission to deliver great value to our customers. We should be leading the change—it is in our DNA. Instead, we run from it, because it challenges all the rules of our brick-and-mortar world. And it makes us, I’m sad to say, defensive.”

- The tyranny of millions of units and supranormal profits. Incumbents are usually so big they are used to thinking in millions and billions of units. Their operations derive the highest efficiency from scale and everyone is encouraged to focus on scale initiatives. New ideas, which demand a period of ramp up, are perceived as a distraction because uncertain lot sizes and the need for endless adaptation don’t take advantage of current skill sets. In addition, the incumbent always has a core of the core—a specific sets of products or services that enjoy exceptional—or supranormal—profits, usually because of some combination of customer stickiness, pricing power, or low costs due to scale and amortization. That’s great. The problem is incumbents use these product lines as the lens through which they judge new innovations. This creates a numerator-denominator problem. Incumbents evalutate innovation in its early years by comparing it to their core business, which is in its mature years. That leads to constant “no’s” since the idea is immediately perceived as dilutive. Insurgents give weight to future potential over current cost. They compare the innovation at its full potential against the current business, which leads to the right kind of “yes.” You can’t blame the incumbent for having a bigger denominator. But you can blame it for using the wrong numerator. Doing so stacks the deck against innovation based on generalized pessimism about the future.

- The tyranny of “the sky is falling” forecasts. The incumbent has oodles of industry expertise, and over the years, internal experts have presented leadership with dozens of forecasts that “the sky is falling.” Through heroic action, the incumbent has delayed these doomsday scenarios—for now, anyway—and management starts to ignore new data even as the data starts to prove that some of the worst predictions are coming true, albeit at a slower pace than originally thought. Then, insurgents begin to exploit these long-term trends and the incumbent is the last to notice. It’s as if an executive team has been presented with 10 years of predictions about price collapses in their industry but is totally unprepared when the collapse actually arrives. The team has wasted years not supporting new ideas to drive down costs or develop alternative sources of revenue. And when the pressure to act finally becomes unbearable, a chaotic effort to slash prices becomes unbelievably expensive. The costs of being a future taker when the trends work against your core business can be catastrophic. The benefits of being a future maker and exploiting trends proactively can be extraordinary.

The list of tyrannies is a long one and begins to explain the paradox of the great incumbent downfalls—in many cases, the organization itself had generated the disruptive ideas that were exploited by the insurgents. The ideas were there but the incumbent didn’t act because these ideas were dismissed as mice nuts. Go back and read those failed incumbent stories— they are filled with the frustrations of employees who never got the attention of senior leaders who were more concerned about protecting yesterday’s gains than preparing for tomorrow.

Idea screening. Every company, whether future maker or future taker, must funnel a long list of potential ideas into a shorter list before deciding which will receive investment and management attention. The real difference between incumbents and insurgents is where senior managers decide to spend their time. At insurgent companies, senior leadership tends to get involved early, at the top of the funnel, taking an active role in deciding which potential ideas deserve scarce development resources. One founder we work with uses a “Power of 10” filter, meaning he won’t greenlight an idea unless his team is willing to spend 10 times more energy and resources on making it happen than on any other project. This may seem like a tough hurdle, but in fact it reflects an optimistic view of what’s possible. For insurgents, senior leaders must be in a discussion of disruptive innovation from day one, to help build and nurture the idea and then decide: Either we go for it, or we fold. And since the senior leader is a future maker, the bias is to play another card if that promises to keep the idea big. Plenty of ideas get killed, of course, but top leadership’s early, emotional commitment to the best ideas ensures that they get bigger as they graduate through predictable stages, each of which requires more innovation and brainstorming.

Idea screening at the typical incumbent is very different. Senior leaders tend to get involved at the skinny end of the funnel and want it to be, well, a funnel, screening out lots of bad ideas. They abdicate the early process to staff members, which means that a lot of organizational energy is devoted to figuring out which ideas won’t work. A “good” process starts with lots of little, undeveloped things at the beginning, adds a rigorous process to kill most of them through the funnel, and then one or two still-undeveloped ideas emerge at the end. Given the low output, leaders learn to get involved only when a good idea emerges. But, unfortunately, you tend to get what you pay for. One consumer-products CEO I spoke with at a conference recently said that the single best thing he had done to improve innovation was to shift his attention from the end of the funnel to the beginning. The CEO felt he could have far more impact by influencing what went in the funnel, rather than trying to reshape the small ideas that emerged at the end. Future makers believe they will win—and the senior leader is willing to “spike” in terms of devoting his or her time and attention to a big idea. Future takers are pretty sure they will lose, and the senior leader is far more willing to “smooth” his or her involvement across a wide range of small bets to control the downside.

Commercialization and scaling. Insurgents live in a resource-scarce environment, so they must be selective about opportunities. But because they view each disruptive innovation as a transformative opportunity, when they are in, they are in—believing there’s no point in investing in an idea unless you’re going to win. Incumbents are far more bipolar. On the one hand, when it is time to scale a new business, most ideas suffer from benign neglect. The average leader would rather let the new business stumble along for a while (confirming that it wasn’t a good idea) than risk trying to make the business 10 times bigger. Allocations to new business areas are almost always viewed as bad career moves. It is not that you will fail spectacularly going after the big prize; it is far more likely you will drift into obscurity in a tiny business no one cares about. On the other hand, some ideas are so BIG, so cannibalistic, so evil, so anti–the core, so certain to spell the doom of everything good and safe, that the safe thing is to kill the idea as a profound threat. There never seems to be a middle ground—the new business concept is so small and trivial, with so little chance of success, the thinking goes, that we shouldn’t resource it. Or, we should starve it for resources because it is a massive threat to everything we stand for. Notwithstanding the bipolar nature of motive, the impact is the same—the new business ideas die slowly and painfully, reconfirming to all that the future is an ugly place.

The subtle (and not-so-subtle) differences between how insurgents and incumbents treat innovation start with how ideas are discussed, evaluated, built and commercialized. Incumbents view the future as negative, draining away revenues, profits and market positions held today. New ideas are small and distracting relative to the challenge of protecting today’s business, which is particularly annoying because the organization seems to create so many of them through the natural course of business! Moreover, ideas can’t be nurtured by an organization that thinks in millions of units and enjoys (for now) supranormal profits. For incumbents, innovative or disruptive ideas are almost always unformed and seem vague and intangible relative to the clarity of the core. It is better to build a robust funnel to kill them, and ensure that leaders don’t get involved until the end. Finally, it is best to let the few ideas that make it trickle along—don’t announce failure, but don’t risk relevant success.

For insurgents, the future is positive, the source of all new revenues, profits and market positions. For them, the thinking is: A new big, bold idea can double fortunes, and we should either devote attention to build the idea into something real, or we should shut it down quickly. We can’t afford to spread our resources smoothly—we will survive by spiking resources to support the best ideas. And if we’ve committed, let’s go for it; let’s make the better future and bet it all.

A shift in mindset can change everything.