Report

This article is Chapter 10 of Bain’s global Technology Report 2020. Explore the contents of the report here or download the PDF to read the full report.

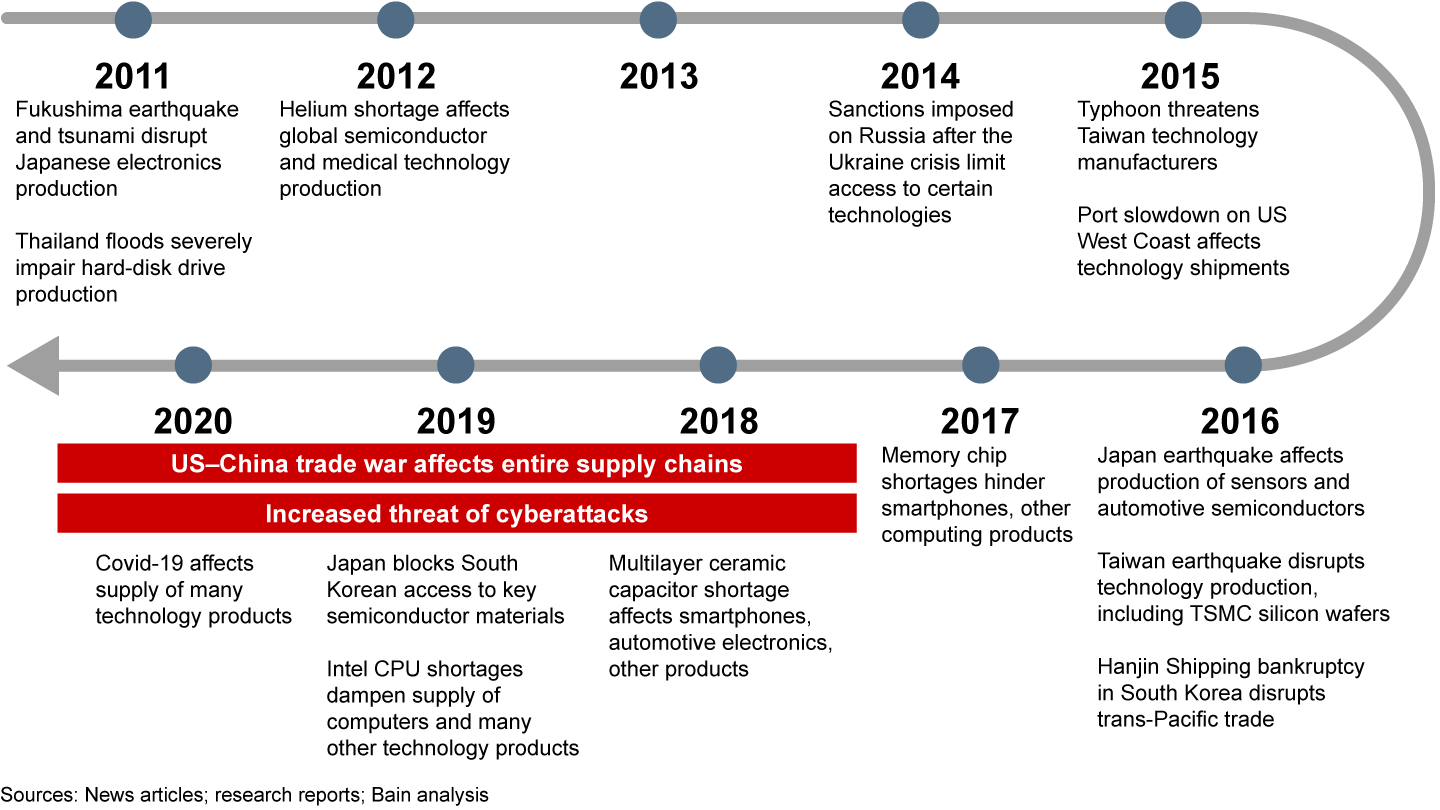

When Covid-19 blew up supply chains around the world, technology executives felt that familiar pit in their stomachs. Although the nature and scale of this pandemic is an unprecedented tragedy, it was the latest in a series of significant blows to the technology supply chain over the past decade (see Figure 1).

Most technology companies have dealt with each of these convulsions in a painful, brute-force manner. In response to Covid-19, operations teams spent months in war rooms manually tracking material shipments, trying to map Tier 2 and 3 suppliers, and shifting production to new locations such as Vietnam.

Those kinds of actions don’t fix the cracks at the foundation of supply chains. At best, they just blunt the impact of disturbances.

Covid-19 has pushed technology supply chains to their limit. Lockdowns and the disease’s spread have squeezed factory production and created headaches for shipping and other logistics. The pandemic also threw typical demand patterns for technology products off-kilter in the short term. Some segments saw an uptick, such as work-from-home equipment, while others nosedived, such as technology components for the automotive industry.

All of this has caused massive chaos for supply chains. Consider this: In February, during the height of the lockdown in China to combat the virus, the country recorded its largest one-month drop in manufacturing activity, as measured by the Purchasing Managers Index. The PMI decreased from 50 (indicating a balance between expansion and contraction) in January to a record low of 35.7.

How did we get here? For the last 30 years, technology firms have wrung out supply chain costs and trimmed as much fat as possible by disaggregating the various steps of the value chain, concentrating each step with a limited number of companies and geographies to improve economies of scale, and reducing inventory across the journey.

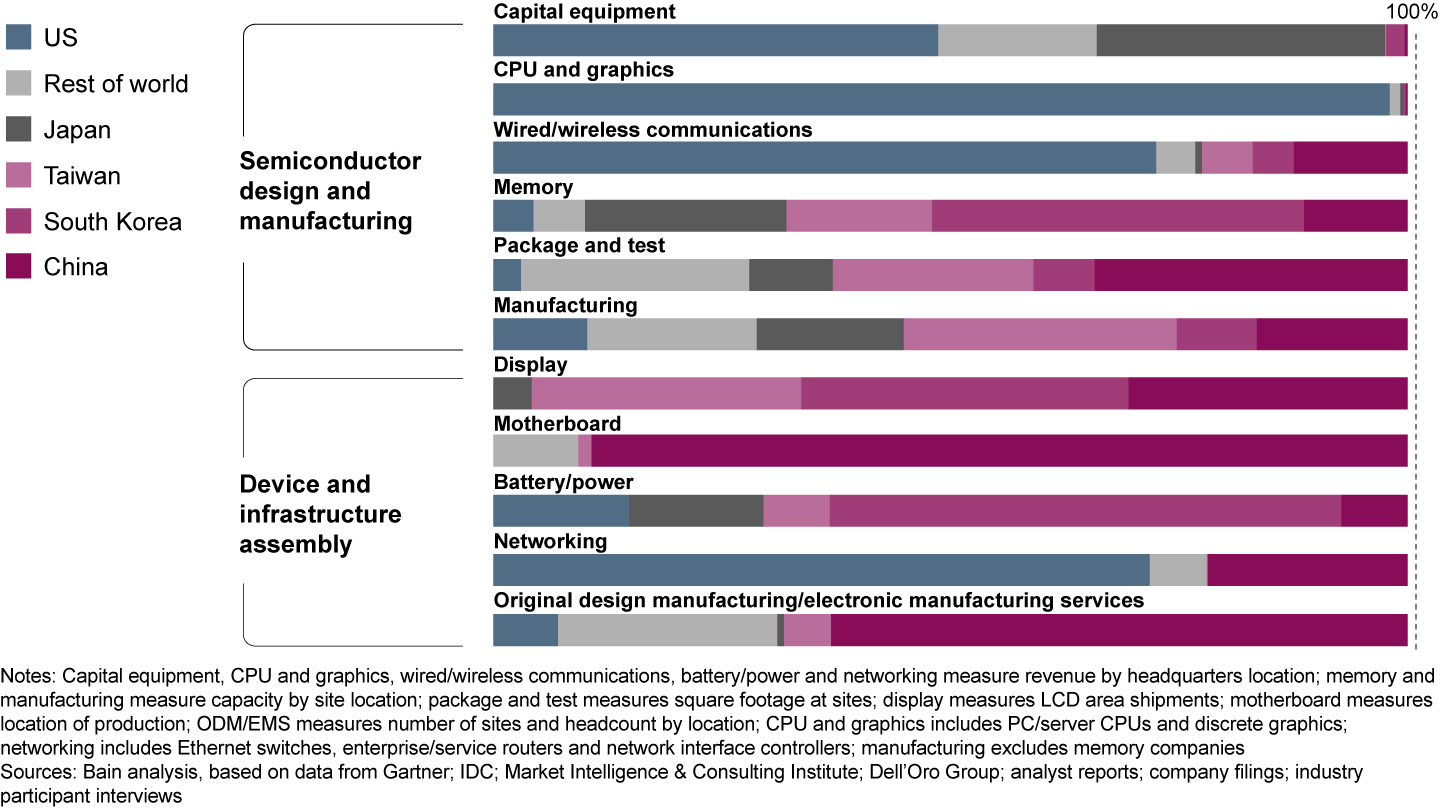

This has made technology supply chains extremely efficient in a normal economic climate. When disaster strikes, they break down. The geographic concentration of production has created single points of failure, such as a reliance on China for motherboards and electronics manufacturing services, and a dependence on the US for semiconductor equipment, central processing units and graphics cards (see Figure 2).

In 2011, terrible flooding temporarily crippled supplier operations for hard-disk drives in Thailand, the largest producer behind China. That caused a global shortage of hard-disk drives that created ripple effects throughout the computer industry.

Making supply chains more resilient is challenging because many technology components have single suppliers due in part to high capital expenditures and R&D requirements. The rapid pace of innovation further weakens supply chains because inventory quickly becomes obsolete and a “winner-takes-most” model winnows the number of suppliers.

The writing is on the wall now. The pandemic, combined with growing trade tensions, spell continued volatility for technology supply chains for years to come. Deutsche Bank estimates the US–China trade war could result in companies spending about $1 trillion over a five-year period to move supply chains out of China. Rising global trade tensions have affected specific companies, including Huawei Technologies, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and Apple. The tensions have also impeded entire industries, such as Japan cutting off South Korean memory chip companies’ access to fluorinated polyimides, photoresists and hydrogen fluoride, three materials critical to production.

What’s become obvious is the frequency and scale of these disruptions to supply chains will only continue to grow. That calls for striking a new strategic balance in technology supply chains. Low cost and efficiency are still crucial, of course, but resiliency has become vitally important. Leading technology companies are intently engaged in finding ways to build more flexibility into their sourcing and supply chains, recognizing both the downside risk and the upside competitive potential of maintaining product flows when the next disruption crops up.

A good starting point for executives committed to revamping their supply chain is to look at it through their customers’ eyes: What do customers really want? What would make us indispensable to them? What operational capabilities differentiate us from the competition? How can we build those things into our supply chain to make it more resilient and effective? Companies that customize their supply chain, say, by quickly ramping up local production to improve turnaround time, can improve resiliency and turn the supply chain into a competitive advantage.

Looking at successful strategies across the technology industry, Bain has identified five common attributes of resilient supply chains: an agile network structure, digital and secure operations, real-time visibility, practical analytics and an empowered organization (see Figure 3).

For example, an agile network of contract manufacturers can help original equipment manufacturers navigate changing tariffs. For many companies, a “China-plus-one” strategy that sources supplies from China and a second location makes sense, but where and how to manage the “plus one” is challenging.

Trade tensions and other destabilizing events are forcing manufacturers in China to make significant adjustments to their businesses as well. Many multinational corporations have relocated some of their production out of China in recent years, in part due to rising labor costs. These companies’ share of China’s overall manufacturing revenue dropped from 29% in 2008 to 22% in 2019, according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China. Covid-19 and the escalating trade war are accelerating that exodus. Many China-based manufacturers have responded by focusing more on supporting demand from the country’s local businesses and consumers. At the same time, new trade restrictions have forced some Chinese manufacturers to find alternative sources of equipment and materials they previously imported from the US.

Some companies have weathered crises better than others because they took steps beforehand to make their supply chains more resilient. The Bosch Group, a German-based global supplier of technology and services for automotive, consumer goods and other sectors, has used its agile network structure during the Covid-19 crisis to seamlessly reallocate production to facilities less affected by labor shortages and other repercussions of the pandemic. This structure also enabled Bosch to nimbly adjust output to match reduced demand from auto manufacturing customers that had cut their production in response to the pandemic. Similarly, Bosch used a system of sensors and software to more effectively monitor inbound supplier shipments and quickly source components as it identified shortages or shipment delays. Digital tools have also helped workers, especially equipment technicians and other service personnel, stay connected and keep facilities running as smoothly as possible.

The final piece of a successful supply chain strategy is quantifying it. Leading companies establish clear metrics for assessing resiliency and adaptability, and they track those as rigorously as unit costs and inventory. That helps them monitor the return on investment and compare their efforts with competitors. The leaders pursue resiliency measures likely to deliver the most value, while still balancing those investments against the company’s risk profile.

The leaders also use thorough scenario planning to stress test their strategy and make sure they’re as ready as possible for the next crisis. It might sound excessive, but imagining and preparing for a worst-case disaster that seems inconceivable today could pay off down the road. What if a single event wiped out a huge chunk of the business overnight? That’s the kind of shock TSMC faced this year, when new US export controls pushed the company to stop taking product orders from China-based Huawei, which accounted for about 15% of TSMC’s annual revenue. TSMC executives have said they expect demand from other customers to make up for it, but that’s still a massive change that requires adjustments on the fly.

Executives embarking on a supply chain transformation should go into this journey with clear eyes: Putting resiliency above efficiency will come at a cost. It will likely be more expensive to buy some components from a second supplier outside of Asia or to move supplier operations closer to manufacturing and assembly facilities so they’re a truck drive away instead of a plane ride.

Nevertheless, when the next disaster strikes, executives will be glad they built more resiliency and adaptability into their supply chain. That goes for their customers, too.