Founder's Mentality Blog

Once you get an idea in your head, it feels like everything you read is somehow related. Specifically, the more we’ve started dividing business leaders into what we call “future makers” and “future takers” (we’ll explain lower down) the more I seem to find evidence, albeit in odd places, that the distinction is important. So, apologies in advance for the “leaps” here.

In his recent book, Sapiens, a Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari sets out to explain why the relatively small geographic area of Europe managed to spark a “scientific revolution” that transformed the global economy over the next 500 years. “In 1775, Asia accounted for 80% of the world economy,” he notes. “The combined economies of India and China alone represented two-thirds of global production. In comparison, Europe was an economic dwarf…How did the people of this frigid finger of Eurasia manage to break out of their remote corner of the globe and conquer the entire world?” His answer is two-fold: First, the Europeans launched an era of discovery. Second, they nurtured the world’s pre-eminent economic system—capitalism.

Harari argues that maps help tell the story of the era of discovery. Many cultures drew world maps long before the modern age, he notes. But these maps simply left out unknown areas or filled them with “imaginary monsters and wonders,” giving the impression that the mapmakers were familiar with the entire world. During the 15th and 16th centuries, this changed. “Europeans began to draw world maps with lots of empty spaces—one indication of the development of the scientific mind-set,” Harari contends. “The empty maps were a psychological and ideological breakthrough, a clear admission that Europeans were ignorant of large parts of the world.”

About the Founder's Mentality

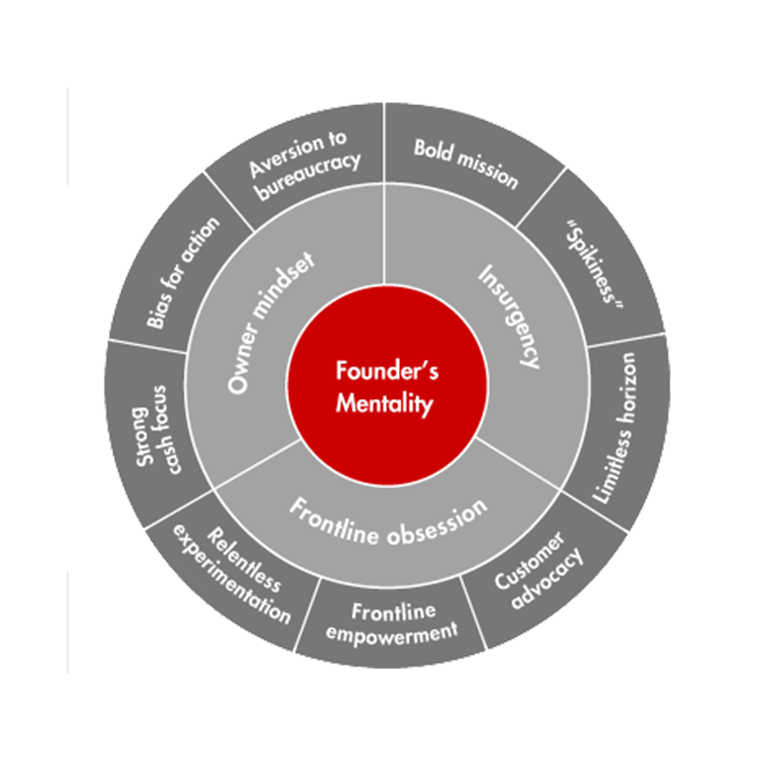

The three elements of the Founder's Mentality help companies sustain performance while avoiding the inevitable crises of growth.

Regarding the rise of capitalism, Harari writes that the critical change was that Europeans began to believe that the future would be better than the past. “The idea of progress is built on the notion that if we admit our ignorance and invest resources in research, things can improve,” he argues. “Over the last 500 years the idea of progress convinced people to put more and more trust in the future. This trust created credit; credit brought real economic growth; and growth strengthened the trust in the future and opened the way for more credit.”

These two forces led to an explosion in exploration and conquest, scientific discovery, new capital for businesses and, ultimately, the scientific revolution that put Europe and the US atop the world economy by the middle of the last century. One can argue whether all this was a good thing for humankind. Harari, in fact, suggests average human welfare has suffered since the hunter-gatherer era. (It’s also hard to dispute that the era of discovery had horrific consequences for native peoples especially in Africa and the Americas.) But in terms of knowledge and wealth creation, the results are self-evident— acknowledging the “white space” in our knowledge and believing in the future creates economic growth.

In this narrow sense, at least, there are striking parallels between Harari’s summary of what drove the scientific revolution and the arguments PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel puts forward in his new book, Zero to One: Notes on Start-ups or How to Build the Future. Thiel argues that leaders and investors in start-ups should focus their resources and passions on building “creative monopolies”—new businesses that can dominate a new market for the benefit of customers and investors. He worries that we’ve lost the desire to dream of and invest in truly big ideas, noting that a) we’ve stopped believing in “secrets”—or new ways to solve customer problems—and b) we no longer devote the time to plan for a bolder, more transformative future. Thiel’s notion of secrets is similar to Harari’s idea of maps with empty spaces. And Thiel’s argument that we should recommit to planning for a bigger future (as opposed to evolving and adapting randomly) is similar to Harari’s notion that to grow economically, you first have to commit to the notion that things can get better.

With radically different subject matter, both authors, I think, make the case that breakthrough progress demands a belief that you can shape the future, not just live it as it comes. In other words, those who make breakthrough progress view themselves as future makers, not future takers. Similarly, the more we explore the fundamental differences between corporate leaders with an insurgent mindset and those with an incumbent mindset, the more we think the difference is rooted in attitudes toward the future.

Those with an incumbent mindset are future takers. They either view the future passively—which means they have no power to shape it—or they view it defensively—which means they must fight or delay it. Incumbents want to protect current profits in a world where prices seem to be falling for their core offerings. They are trying to hang onto current customers as traditional competitors and new insurgents bombard them with predatory offers or (gulp!) better ones. While they see innovation and disruption occurring at the edges of their industry, they don’t see this as a good thing for them – turbulence erodes profitability, innovation marginalizes their current product offerings. The future is not better.

Those with an insurgent mind-set, on the other hand, are future makers. The future brings disruption and innovation and they have faith they can capitalize on these new developments far better than the industry’s future takers. Chaos is a good thing. Innovation is a good thing. The future promises to be far better than today.

The war between future makers and future takers takes place daily—the newspapers are filled with their skirmishes. But because change occurs in small increments, it is difficult to see the truly seismic shifts until it is too late. I was reminded of this (I warned you about those leaps) when my university-age children introduced us to a recent Reddit comment trail entitled “Blow my mind in one sentence.” The idea is for folks to compete against each other to produce the most “mind blowing” ideas (leading to a lot of interesting dinner table conversations with the kids). One example: “What happens when Pinocchio says, ‘My nose will grow longer?'” Another seems oddly relevant to the discussion of future makers vs. takers: “One day your parents put you down and never pick you up again.”

Needless to say, the sentence itself is rather sad and poignant (and we’ve tried to pinpoint the day with our three giant children). But it also speaks to how major change sneaks up on you. I’d argue that the management teams of most great companies go to bed one night as future makers and wake up the next morning as future takers. At some moment in time, and it is probably different for each leader, the switch happens—the bulk of his or her energy shifts from embracing the future and seeing it as an asset, to fighting the future and seeing it as a threat. The leader moves from aggressor to defender, from revolutionary to conservative. From insurgent to incumbent.

Over the course of several upcoming blog posts we will explore why it is that incumbents find it so hard to thrive in turbulence and offer some ideas about how they can do a better job. We will explore why, despite their scale and scope, they aren’t the natural candidates to transform their industries and how they can improve their odds.

But before going there, we wanted to offer one simple notion. At its core, the problem facing incumbents is a mindset issue. The problem they face is their attitude toward the future. At some point, the leaders of these companies shift their attitude about the future. They go to bed future makers and wake-up future takers. And this affects everything.