Founder's Mentality Blog

I’ve devoted most of January and February to leading roughly 20 workshops in the US and Europe on a single topic: How do large incumbents recover their Founder’s Mentality®? The next few blog posts will be about key themes raised during these workshops. I’ll start here with the topic that came up most often: How can leaders keep the spirit of the founding period alive through stories and symbols? We started to call this “the iconography of founders.”

Iconography is the use of symbols to convey meaning. For our purposes, we’ve stretched the definition to include symbols and stories. We defined the iconography of founders as “the actions taken to teach employees about the values of their founders (or of the company’s founding period) through stories or symbols.” I’ve become a nerdy student on this topic over the last eight weeks and in this post will try to 1) set out the different types of iconography we identified, 2) explore good and less good ways to use these stories and symbols, and 3) leave you with a few questions.

During the course of the workshops, we collected examples of five types of iconography:

- Birthplaces: Let’s start at the beginning. It is remarkable how many leaders work to keep the spirit of the founder alive through the preservation (and celebration) of company birthplaces. From Sam Walton’s first store in Bentonville, Arkansas (Walton’s 5&10) to the HP garage in the heart of Silicon Valley, the goal of this type of iconography is most often to demonstrate the humble origins of the company (emphasizing values of simplicity, humility, focus on the customer, hands-on role of senior leaders, etc.) while also emphasizing the importance of working together and winning against the odds.

- Artifacts: Wells Fargo has the Wells Fargo stagecoach, which makes hundreds of appearances in the banking company’s markets throughout the US (reminding customers and employees alike of how the company’s history informs its values and brand). Ad agency Leo Burnett has its ubiquitous apples (reminding folks of the founder’s persistence in the face of skeptics) and its eraserless pencils (there are no bad ideas). Pixar has its Luxo Jr. desk lamp (which ties each new film to the one that started it all). These artifacts give management the excuse to tell stories to employees and, more important, they inspire employees to tell founding stories to each other. Unlike birthplaces, artifacts can be distributed widely across the company’s global offices, ensuring continuity and consistency of storytelling.

- Sacred tablets: OK, they aren’t really tablets. But these documents contain a critical list of values, principles or ways of working. They spell out the mission statement or collect a set of founder quotes. The words are the story here. From AmBev’s 10 principles to Lego’s principles of play to Bain’s mission statement, these lists give leadership a chance to talk about how they were created and what they mean today.

- Parables: These are the company’s defining stories—tales about “giving it all,” doing what is right for the customer (often against the interests of the company) or taking time to help a coworker who was about to fail. Parables are often uplifting (a great customer feedback story) or cautionary (the story of a CEO firing someone on the spot for not looking after a customer). In a world of social media, they are increasingly shared on YouTube and lead to deep discussions about what the founder stood for. Here are three great ones: Sam Walton’s hula dance, Steve Jobs’s “Focusing is about saying no” and Leo Burnett’s “When to take my name off the door.”

- Rites of passage: These are the trials or formative experiences the founder endured and that all leaders have to go through. Many leaders at Unilever will talk fondly about their training at Four Acres (where they often see pictures of their current bosses on the walls, attending similar sessions as much younger managers years before). Whether it’s training or starting on the front line or working in call centers during peak times, these rites of passage ensure that everyone goes through the same experiences—most often those that the founder went through in starting the company.

In addition to collecting examples of iconography we also used part of the workshops to assemble a list of best practices for how to use symbolism in rebuilding the Founder’s Mentality:

- Don’t claim the past was perfect. There’s always the danger with any story that it glorifies the past. This is a problem. First, such glorification is seldom true, but more important, it focuses the story on the preservation of what came before, rather than on the need to build a better future.

- Use “living” symbols. The best stories and symbols leave room for the current generation to contribute. I think this is why so many companies turn founder stories into awards—the actual symbol is the long list of winners and their stories. As an example, CavinKare created the Chinnikrishnan Innovation Award, which reminds everyone of the founder’s original insurgent mission philosophy: “What the rich man can enjoy, the poor man should be able to afford.” Southwest Airlines fills the halls of its headquarters with pictures and examples of its annual Halloween parties—where employees role-model a culture of fun and not taking themselves too seriously. Rather than celebrate the accomplishments of the distant past, living symbols capture the spirit of the founder in the actions of current employees.

- Use storytelling to “train the trainer.” It is far better to tell stories to your people so they can go forward and tell more stories. You are training the trainer, who in turn will tell others.

- When all else fails, tell stories of failure. Everyone mentioned this. It is important at times to talk about when the company or, better yet, you personally, did not live up to the standards the founder established. There is a humility and honesty to failure stories that encourage learning and encourage storytelling. As Bill Gates says, “It’s fine to celebrate success, but it is more important to heed the lessons of failure.”

I’ll end with a few questions:

- How do you talk about the insurgency? What are the symbols and stories you use to tell the story of the insurgency? Which stories keep customers, and the “kings” who serve them, at the heart of your culture?

- Are you training new storytellers? How do you make sure these stories will outlast you, outlast the current generation? Are you helping your people develop the next set of stories? Have you helped them create and distribute new symbols?

- When was the last time you told a story of failure? Is your culture built on the mythology of a “better past” or the promise of an extraordinary future the current generation will shape?

About the Founder's Mentality

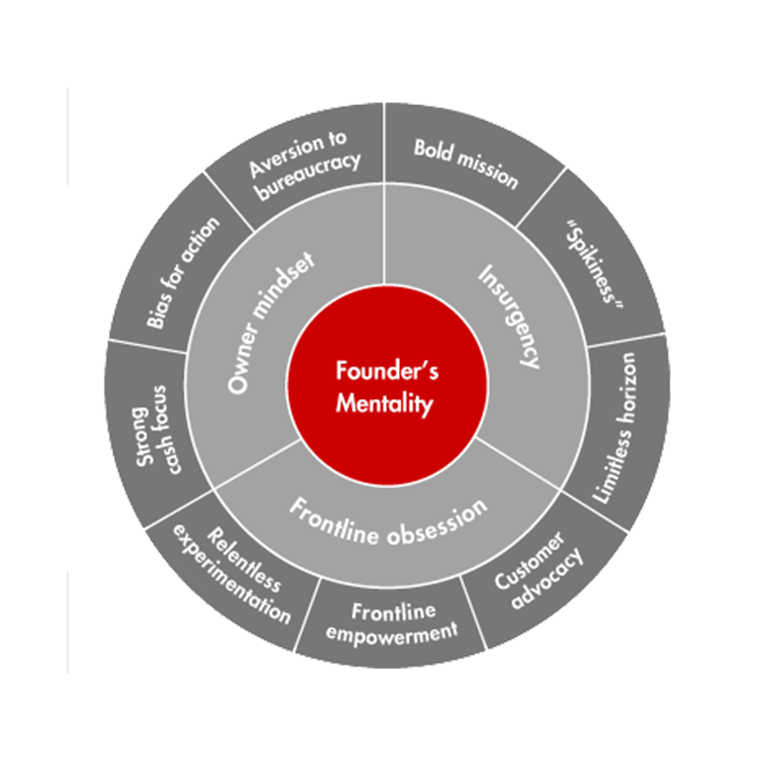

The three elements of the Founder's Mentality help companies sustain performance while avoiding the inevitable crises of growth.