Etude

En Bref

- When the strategy is sound but performance has stalled, the problem may lie in how the organization orients around the strategy, executes against the strategy or both.

- The Organizational Navigator diagnostic approach helps executives understand their organization’s starting point so they can set a practical course for better results.

- Our analysis finds that six organizational outcomes enable strong business performance.

- Companies often exhibit one of five organizational patterns, and once executives understand which pattern they fit best, they can determine where to invest and which organizational levers to pull in order to get back on track.

A large technology service firm with a history of strong execution has come up short for years on its growth and profitability targets relative to many competitors. While the senior executive team agrees on the strategy, they have not taken the actions needed to orient employees to that strategy. They deploy the organization’s strong marketing, program management and financial capabilities against a constantly changing set of operational objectives and metrics. The whiplash this management team creates leaves many employees exhausted and confused. This senior team spends more time praising their execution against near-term deliverables than discussing how to align the organization against the long-term priorities.

An industrial supplier struggles at the other end of the spectrum. Despite having a solid strategy that the organization already orients around, senior executives insist on constantly having multiday strategy offsites and avoid more pressing concerns about weak execution against customer expectations. The senior team spends a lot of time discussing which acquisitions to make and which new technologies to invest in, and relatively little time on how to better deliver products on time and under budget.

Halting or misguided attempts to improve performance are not uncommon. For companies that feel stuck despite having sound strategies, it is often unclear whether the problem lies in how the organization orients around the strategy, executes against the strategy or both. So companies flounder as they throw more energy and resources at remedies for the wrong problem. Instead of addressing what ails them, they focus on what they know and do best. This predicament can become even more pronounced when companies try to migrate their business model, or market conditions shift dramatically or upstart competitors begin taking share.

Fixing Poor Organizational Performance

Many companies flounder when they try to cure what ails them. To succeed, pinpoint your specific problems before trying to fix them.

Dealing with an organizational dysfunction starts with a diagnostic that uncovers the root causes of the symptoms. Once you uncover root causes, proven remedies usually exist. To oversimplify, if a company has an orientation problem, the solution may reside in getting senior leadership better aligned, clarifying roles and accountabilities, or reducing organization priorities down to the two to three priorities most critical to the stated strategy. An execution problem may require addressing major talent gaps, poorly performing systems, a lack of focus on cost and performance or all of the above.

Executives thus benefit from taking a step back to understand the true nature of the problem that needs repair, rather than jumping to an answer that focuses on areas where they feel most comfortable (and where they likely already perform reasonably well). A diagnostic approach that we call the “Organizational Navigator” can help executives understand their starting point so they can set a practical course for better results. The Organizational Navigator assesses where their organization is strong, where it is weak and, critically, where it should focus to have the greatest effect in improving its business performance.

Connecting organizational performance to business performance

Over the past 18 years, Bain & Company has studied hundreds of companies around the world, and our research has uncovered what great organizations look like. We have also surveyed more than 1,200 companies globally across industries. Our experience and the data from the survey both point to six organizational outcomes that together account for high performance (see Figure 1). These high-performing organizations are:

- aligned with the company’s strategy;

- capable of executing strategy with the right talent, processes and tools;

- effective at making and executing critical decisions;

- adaptable in the face of rapid change;

- efficient in realizing the benefits of scale and scope; and

- inspired to go the extra mile

The better a company’s performance along these six dimensions, the greater the odds that it will be a business performance leader—that is, performing in the top quintile relative to industry peers along revenue growth, profitability and total shareholder returns, over a five-year period. Companies that are top performers across these outcomes are about six times more likely than peers to be business performance leaders.

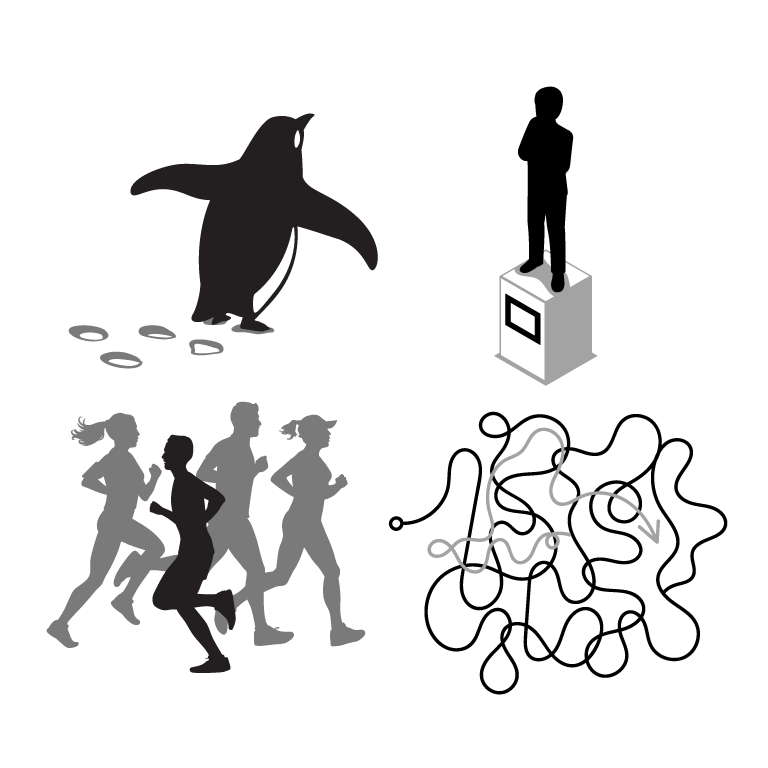

For the vast majority of companies—the roughly 90% with lower business performance—it’s critical to make a careful assessment of their starting point. And while each company’s situation is unique, our analysis does reveal patterns that can be useful for executives trying to decide where to invest. Based on how companies perform on each of the six dimensions, we grouped these lower performers in four diagnostic patterns (see Figure 2):

- Focused waddler. Comprising 40% of respondents in our analysis, these companies exhibit a strong sense of direction, but they typically have one of two major problems that weaken their execution. Some lack the requisite capabilities to operate efficiently and consistently. Others may have decent capabilities but have complex decision-making processes that slow things down.

- Aimless runner. This 30% of the total group consists of capable executors that still cannot deliver on their strategy because the organization has not aligned to the strategy, creating confusion and competing priorities. They work without orientation.

- Happy statue. These companies, 10% of the total, often have good employee engagement and satisfaction, yet lack either clear orientation, strong execution or both.

- Stuck in a shambles. Another 10% of companies fall in the fourth or fifth quintile across all dimensions. They lack orientation, execute poorly and suffer from unhappy employees.

Let’s look in more detail at each group, with options for attending to their distinct problems.

Focused waddler

Some companies have a clear strategy and successfully orient employees around the strategy with proper communication, resourcing and incentives—yet they seem unable to deliver on the strategy. The problem may stem from a lack of key capabilities or skills, especially when the strategy evolves. For instance, if a company decides to ramp up cross-selling, it would need a strong account management capability. Founder-led companies that have grown rapidly often fall into this category.

A mobility technology company found that in the process of growing quickly it had started many ad hoc processes and workarounds without first building the necessary infrastructure and capabilities. Complicating matters, while it was composed of two somewhat unrelated businesses, the corporate center had started integrating activities across the two out of concern that neither unit was recruiting the right talent. Executives reconsidered this approach. They realized that growth would depend on shoring up technology and operations infrastructure and undoing some of the shared services. They also shifted more accountability to the business units, which were better placed to make the right trade-offs because they were closer to customers.

Other companies that fit this pattern suffer from unnecessary complexity in their processes, or confusion over who is accountable, making it difficult to operate efficiently. People may share the same goals, but when it comes time to instilling cost disciplines and improving operations, bloated or duplicative processes get in the way.

For the problem of weak capabilities, the most useful response starts with an assessment of which capabilities matter most to delivering on the strategy, and what gaps exist in those capabilities. Then the company can begin systematically addressing those gaps—bringing in new talent, upgrading systems and tools, revisiting processes or some combination of these. If the gap stems from overly complex processes the best answer is often a zero-based redesign—a onetime, blank-sheet approach to streamline work processes, simplify the organization, unlock savings and unlock time and energy.

Aimless runner

Well-oiled, lean execution machines can be wonderful to behold. Fast decisions, smooth processes, firm deadlines—all make for solid operations. But those virtues have limited value if leadership has not properly oriented the organization around the company’s strategic direction. In these situations, objectives often shift from one quarter to the next, and the sterling execution of one team might not be consistent with, or even undermine, other teams.

Such companies wind up being less than the sum of their parts, stemming from several possible causes. In some cases, senior leaders might not share a consistent view of success, or they issue vague communications about the strategy. In other cases, they hesitate when managing under uncertainty, changing priorities in haste. They might allow functions or business units to set objectives, but the objectives of one group conflict with those of others. And the organizational structure and accountabilities could hinder collaboration among functions.

A number of possible responses work well in these situations. If the strategy and positioning is fuzzy, invest first to clarify it—then make sure the senior team supports and commits to it. Evaluate the operating model for opportunities to align it more closely to the chosen priorities, through several means: restructuring accountabilities and reporting relationships, or updating ways of working within and across organizational units.

Happy statue

Inspiration is never enough, even at mission-driven companies that invest a lot in their people. For instance, a company may choose consensus over performance, neglecting the power of individual accountability. Even if employees are highly engaged, they may quietly worry that their company has not kept pace with marketplace changes or does not confront slips in productivity.

Still other companies avoid the tough decisions that efficient execution demands. Their investment posture typically focuses on past spending, and favors adding rather than removing roles. It would be more fruitful for them to build capabilities that would improve performance.

So how can companies create a performance-oriented culture without losing inspiration? To start, it’s essential for senior leaders to articulate a compelling case for change, rooted in the organization’s underlying mission and history.

At the same time, they should assess the operating model, particularly whether it needs an overhaul to perform well in the future given how the relevant markets are evolving. They can also consider zero-based redesign, mentioned earlier, as a way to realign the investment posture with the main sources of growth. And regardless of the specific changes required, senior leaders will want to incorporate employees’ participation when deciding on and planning next steps.

Stuck in a shambles

Now we come to the toughest nuts to crack. For across-the-board underperformers, the biggest question is where to begin, because everything hurts: Costs remain too high, capabilities lag, the executive team bickers, important decisions languish, employees disengage.

Understanding what led to the decline is essential to figuring out how to reverse it. If the root cause lies in bloated teams or processes, which prompt ineffective across-the-board cuts and diminished capabilities, the company should start with zero-based redesign and a complexity audit. On the other hand, if the senior team does not consistently understand or align around the basic strategy, that’s where to focus first.

A leading financial services company has decided to redefine its portfolio and reassess whether years of progressive centralization had really made operations more effective, in addition to bringing cost benefits. Executives found many troubling issues, such as persistent gaps in efficiency and responsiveness to customers, after many activities moved away from the front line. The recovery plan was thoughtfully sequenced to address foundational issues first, such as realigning line-of-business boundaries and closing capability gaps. Only then could the company pursue other opportunities, like technology teams embracing Agile methods, or optimizing the company’s footprint.

In situations like this, organizations are like organisms where all elements are connected and working together, therefore changes in one dimension—say, roles and accountabilities—will often require changes to another, like incentives. Senior leaders need patience to work on the relevant combination of levers that will improve performance.

Setting the right course

The patterns that emerge from our analysis provide general direction. However, an individual company should undertake its own diagnosis to understand its situation in detail—whether the fundamental challenge involves orientation, execution or both, and which areas to invest in to get back on track.

Orchestrating an organizational turnaround can feel overwhelming, with so many issues to sift through and possible levers to pull. The Organizational Navigator approach provides a clear view on the urgent priorities, as well as which areas merit the greatest investment in order to generate superior performance.

Dan Schwartz is a partner with Bain & Company’s Organization practice, Ludovica Mottura is the senior director of the practice and Julie Coffman is a partner and global leader of the practice. They are based, respectively, in Washington, DC, Boston and Chicago.