Report

The gloominess that defines the UK grocery business is well documented. As household budgets tighten, brands compete furiously for their shrinking share of price-sensitive consumer spending, with private labels representing just under half of total grocery sales value, according to Kantar Worldpanel. Meanwhile, multinational consumer goods makers are aggressively diverting their talent and resources from the UK and other Western markets to developing markets, where the prospects for value and volume growth look brighter.

But for makers of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), there’s reason for hope. The year 2012 brought with it a degree of stabilisation in UK shoppers trading down, both in the expansion of private labels and the purchase of regular products when discounted, according to recent research we conducted with Kantar Worldpanel. It’s as if shoppers may have fully adapted their buying habits to the new macroeconomic realities. Now, companies have good reason for optimism. They can use this stabilised environment as the foundation for their future, even in a developed market such as the UK. Companies can build growth by creating new buying occasions for shoppers, encouraging them to trade up to more premium products in the category and increasing market share. Based on this new normal, consumer goods makers can resume investing in strategies for growth.

Some companies are already making the most of these growth opportunities. Quaker Oats boosted sales of its instant porridge by introducing it in an on-the-go pot format, launching new flavours—including special “limited edition” seasonal offerings—and promoting new occasions such as adult coffee breaks. Persil increased its share of the laundry detergent market in large part by investing to win the “war in the store”—appealing to new shoppers at the point of sale, as opposed to focusing on building brand loyalty with consumers. What sets these and other winning brands apart? They pay close attention to the continuing and sometimes subtle changes in shopper behaviour that have a big impact, and they use that knowledge to dictate their moves.

Surprising news: Some companies are delivering both value and volume growth

Undeniably, UK shoppers have changed how and what they buy. To examine the dimensions of this evolving shopper behaviour, we teamed with Kantar Worldpanel. Bain & Company surveyed 3,500 UK shoppers whose spending was representative of the general population. These shoppers included purchasers of all price tiers and more than 450 brands in 17 categories, reflecting around 90% of branded FMCG sales. Kantar continually tracks real-time purchases by 30,000 UK households. Combined, the study gives us the sharpest picture ever of UK shoppers. The profile is invaluable for brands.

Our findings have turned long-held assumptions on their heads, showing how some companies are delivering both value and volume growth. For example, many companies invest heavily to build brand loyalty. But UK’s shoppers are becoming increasingly less loyal to any one brand (see Figure 1). The average UK household purchased 5.6 different brands of chocolate in a single month and four different brands of carbonated drinks. They chose 3.7 brands of frozen food and 3.5 brands of breakfast cereal. There are categories where shoppers showed more signs of loyalty—they chose 1.7 brands of tobacco and 1.9 brands of laundry detergent, for example. But targeting “loyal heavy users” is a loser’s game in almost all categories. Across all categories, an average 50% of a brand’s heavy users won’t be your heavy users next year; they may move on to be another brand’s heavy users.

The message is that attempting to make these customers exclusively loyal to a single brand doesn’t pay—it’s just not how they buy now. Instead, it’s important to appeal not only to your current buyers, but also to shoppers who may not be buying your brand. It’s not enough to recruit new shoppers once and hope they remain loyal. Leading companies know they must win every time at the point of sale.

And there’s more opportunity for that than ever. UK shoppers are making more frequent trips to the store. Our analysis shows that shoppers across the UK made 300 million more trips to the store last year for something that night than they did for their main shopping. Winning companies pay close attention to such breakouts. The reason: They view every trip to the store as a potential shopper touchpoint—a chance to win over new customers. For companies that invest to boost in-store execution—to ensure their products are always available and well placed—it’s 300 million more opportunities to beat the competition.

Winning companies continuously look for the openings created by the nuances of changing shopper behaviour. That’s how Cathedral City is boosting volume and value growth. The dairy company reduced pack size from 400 grams to 350 grams. Although the move is not novel among consumer goods companies, it has enabled Cathedral City to grow full-price sales, outpacing competitors.

Drawing on our research with Kantar Worldpanel and work with FMCG company clients, we’ve identified five new rules that brands like Cathedral City follow to buck the trend.

1. Understand not only your brand’s actual competitive set, but also how consumers really shop a category— then use that as the basis for actionable plans.

Want powerful insights to dictate the right strategy? Look through the shopper’s lens; you’ll more accurately target and pursue the right opportunities. Too many consumer goods companies fail to take this first step.

Consider the difference between how consumers buy beer and how most brewers think consumers buy beer. Our study tracked what actually happens in the store. We found shoppers are less likely to have a particular brand in mind than a specific container (bottle or can) and a specific occasion that would require a predetermined pack size—a six-pack or 12-pack, for example. Only after they’ve decided on the right container and the right pack size do they look at the brand.

For beverage companies, that insight is invaluable. Instead of asking, “Which brand do I compete with?” companies need to ask, “Which 20-can packs do I compete with?” and “What does this mean for how I allocate my promotional spending?” This was one of the key findings from our research: When you look at purchasing decisions from the shopper’s point of view, brands are on more equal footing than most consumer goods companies are willing to believe.

Trouble is, for decades consumer goods companies have built their success by focusing on their brands and how those brands relate to consumers. They spend endless hours asking and answering such questions as, “Who is our target?” “What is our positioning?” and “What do they think of our brand?” Those questions still are important, but the research is telling us that much greater insights come from addressing questions relating to what shoppers actually buy and how they make their choices: “How can I ensure I am top of mind when they physically select a product?” “What else do they consider on the shelf?” “Who am I actually competing against?” “What should I do to fully link my advertising campaign to what the shopper sees in the store?” On this last point, for example, an advertising campaign for toothpaste for sensitive teeth should carry over to the store. Companies should design toothpaste-for-sensitive-teeth packs that stand out from standard toothpaste and then work with retailers to create a distinctive display.

2. Recognise that fewer shoppers are loyal.

Bain research shows that consumer behaviour ranges between two extreme types: loyalist and repertoire. Consumers demonstrate loyalist behaviour when they tend to buy the same brand for a given occasion or need. In contrast, consumers exhibit repertoire behaviour when they buy different brands for a given need or occasion. Over the last few years, both the range of brands sold on offer and the frequency and level of discounts continued to increase; both moves contribute to repertoire behaviour.

Most people display both loyalist and repertoire behaviours, depending on the category they’re buying. Also, the same category may elicit different buying behaviours in different countries. (For a complete look at how repertoire analysis can help a company grow its brand, see the Bain Brief “Introducing the Bain Brand Accelerator.”) As we mentioned, our study of real-time purchasing data shows that UK shoppers demonstrate repertoire behaviour in many categories—despite what they may say in attitudinal studies. Companies are better off understanding and acknowledging this behaviour and activating their strategies accordingly.

3. Invest to grow new shoppers and new occasions for a brand.

Indeed, our recent examination of UK shopper behaviour has outlined the dimensions of consumers’ repertoire behaviour. It’s sometimes a hard message to swallow for brands that have built their success on establishing a loyal following among consumers. As we mentioned, our research also revealed that on average half of a brand’s “heavy users,” who represent the top 20% of sales, won’t be heavy users next year. In some cases, the heavy-shopper retention rate is particularly sobering. For example, one confectioner kept only 24% of its 2010 heavy users in 2011. The rest went somewhere else.

To thrive amid such potential for brand switching, leading companies invest to ensure that their brand is top of mind with those shopping for an occasion. One way they do this is by creating new occasions for using their brand. Here’s a simple example. For years UK shoppers had few options when buying rice: For the most part, they could buy large or small bags of white or brown rice. Uncle Ben’s pinpointed a new opportunity: shoppers who want a quick meal instead of waiting as long as 20 minutes for rice to cook, and shoppers who are stopping into stores to pick up something for that night’s dinner. The timing was right for the brand’s Rice Time, readymade meals with rice, which cooks in 90 seconds. It’s a new use and a new occasion. Instant noodles, too, are winning in the UK, where the cup/bowl category grew 16% in 2012 while plain noodles declined by 7%, according to Euromonitor. Unilever UK’s Pot Noodle, the category leader, saw value sales increase 19%, boosted by Pot Noodles GTi, the premium version containing meat, which was introduced in 2010.

In addition to such innovations, winners strive for high rates of penetration, i.e., the percentage of households in a market buying a particular brand. In this environment—instead of encouraging repeat purchases by current buyers or getting current buyers to spend more—companies simply need to get more households to buy their brand. The good news is that it’s easier to get someone to purchase your product one more time than to get loyal shoppers to buy more of it.

Logical as it seems, the importance of penetration is often overlooked by consumer products companies. But the trend is clear. Because companies will lose current buyers, they urgently need to bring non-buyers into their fold. Persil detergent is a brand that recognised it must attract new buyers to offset the sales they lost as their users opted for competing brands in the highly competitive detergent category. Unilever, its parent company in the UK, has taken a number of steps since 1998 to boost Persil sales, including introducing new formulations aimed at different shoppers. The company developed laundry tablets, a liquid gel version for deep cleaning and a combined scented detergent and fabric softener. Such strategic innovations, combined with tactical moves, have spurred long-term growth. Persil ended up boosting its share while all of its major competitors lost share. Its success came from winning new shoppers, not by getting existing ones to spend more on the brand.

4. Overinvest to win in the store, where most decisions are made. And focus on creating saliency with “above-the-line” advertising to keep your shoppers thinking about your brand when shopping for an occasion.

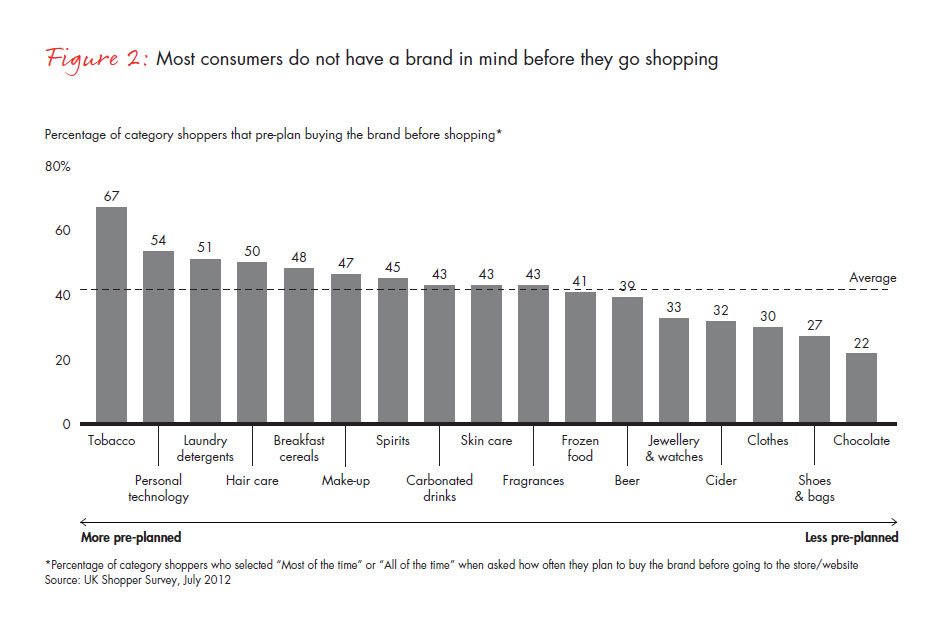

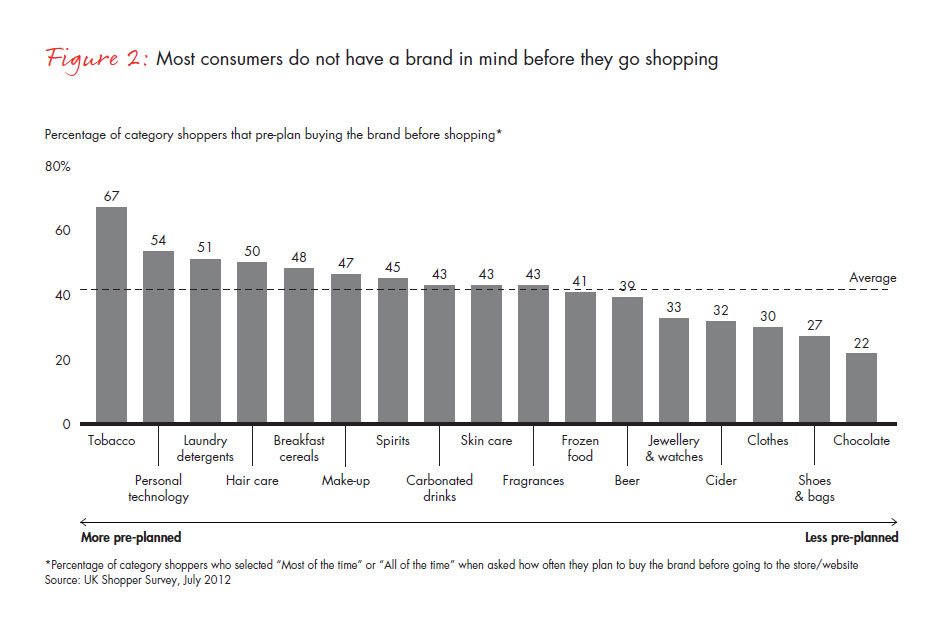

Leaders understand that these two approaches are linked and mutually reinforcing. The research reveals an unavoidable fact: Most UK consumers do not have a brand in mind when they head to the store (see Figure 2). In fact, across the 17 categories surveyed, on average only 41% of shoppers planned to buy a particular brand before setting foot in the store. Pre-planning is highest among tobacco shoppers (67% have a brand in mind) and among purchasers of personal technology (54% know the brand they want to buy). But the majority of shoppers remain undecided, and in some categories the level of indecision is significant. For example, only 27% of shoe purchasers and 22% of chocolate shoppers know in advance the brand they want to buy.

Winning in the store is tied to a key insight: It’s more important that people think about your brand than what they think of it. Even more important: They think of your brand for a particular occasion. Advertising plays a critical role in creating awareness of the brand for an occasion. And companies can reinforce that awareness at the point of sale.

Winners use advertising to promote new usage occasions, not just to build brand awareness or pursue customer loyalty. Consider the massive campaign in the UK by Germany’s Jäegermeister to promote the bitters beverage as a cold shot drink. It’s the brand’s largest promotional effort to date in the UK, its third-largest market behind Germany and the US.

Companies like Jäegermeister start by creating new reasons for shoppers to buy their brand, and then rely on advertising to introduce those new occasions to consumers. Leaders fill the shelves with the best displays so that their brand is the one that shoppers pick out from a crowded shelf of competitors.

To see this point in action, consider the successful resurgence of cider as a popular summer drink. For years, cider sales languished. The drink carried an unfavourable image as a beverage for the older set. Then Magners spotted an untapped occasion—a dearth of summer drink options other than wine or lager. The brand introduced its cider in pint bottles to be poured over ice. In doing so, the brand repositioned cider from its status as something of an afterthought draught beverage to a premium summer drink. New upscale cider was showcased in store displays that were distinct from those for more traditional cider. Magners jump-started the segment and brands like Bulmers joined in, using strong distribution, effective in-store execution and innovations like flavoured ciders to generate rapid growth.

Despite the importance of attracting shoppers inside the store, many companies suffer from poor outlet-level execution. Particularly during key trading periods, they fail to stock the right products in the right stores. There is an enormous dividend for suppliers who are able to consistently activate the right assortment, product display, pricing and promotion—with the channels, customers and outlets that matter most. Rather than focusing on pushing sales overall, sales reps need to give priority positioning to SKUs that sell well in that outlet.

Based on our experience, we’ve found that companies devote a disproportionate share of management time and trade spending on nonstrategic channels. In one instance, the most valued retail outlets represented 60% of sales, but only 30% of investment aimed to reach them.

Investing to target high-value shoppers won’t yield success unless the company understands how important it is to have a consistent strategy across marketing and sales. Too often, consumer products makers struggle with a basic misalignment. The marketing team works to increase sales of high-value products by developing a campaign that defines a winning product assortment, creates in-store displays and improves product visibility. But winning may mean something different to the sales reps and distributors. To maximise their bonuses, they may focus on volume instead of high-margin products.

5. Use promotions to add value to the profit pool. Support with a compelling trade story.

In many repertoire categories, promotions are highly effective in making a brand stand out. In a highly penetrated category like standard cheese, for example, the share of promotions in a particular store directly correlates with a cheese’s share of sales. But skilled promoters ensure the right type of discount, one that adds value to the profit pool; they optimise their trade spending, often the biggest and least understood item on the P&L.

Optimisation starts by peering into the data to understand what really happens when you fund discounts. Most FMCG companies employ software products to track return on promotional spending. But in most cases these analyses fail to properly account for “flows” of volume when products are promoted and can dramatically underor over-state the true return on investment. These flows may be positive when a lower price boosts consumption of the product or steals share from a competitor. But the flows can be negative when a lower price results in “pantry loading” or cannibalisation of sales from other brands within the supplier’s own portfolio. To understand such flows more actively, one company combined consumer panel data with cross-elasticity analysis of supermarket scan data. That way, it was able to overhaul its pricing and promotional calendar, enabling it to increase margins and boost share simultaneously.

Winners realise that promotions almost never result in long-term increases in volume. Sales surges of promoted products often are followed by a dip in sales. And promotions don’t give the brand a halo effect—our research shows that SKUs that aren’t part of a promotion don’t improve. The rule for promotions in the UK’s new shopping environment is to make sure you have the right type of discount. That begins by knowing how well the category responds to promotions. Research shows that deep discounts of 40% or more can often have a negative impact on a category’s incremental sales. Low discounts in the 10% to 24% range, however, can grow a category by encouraging a sufficient number of shoppers to spend more than they otherwise would.

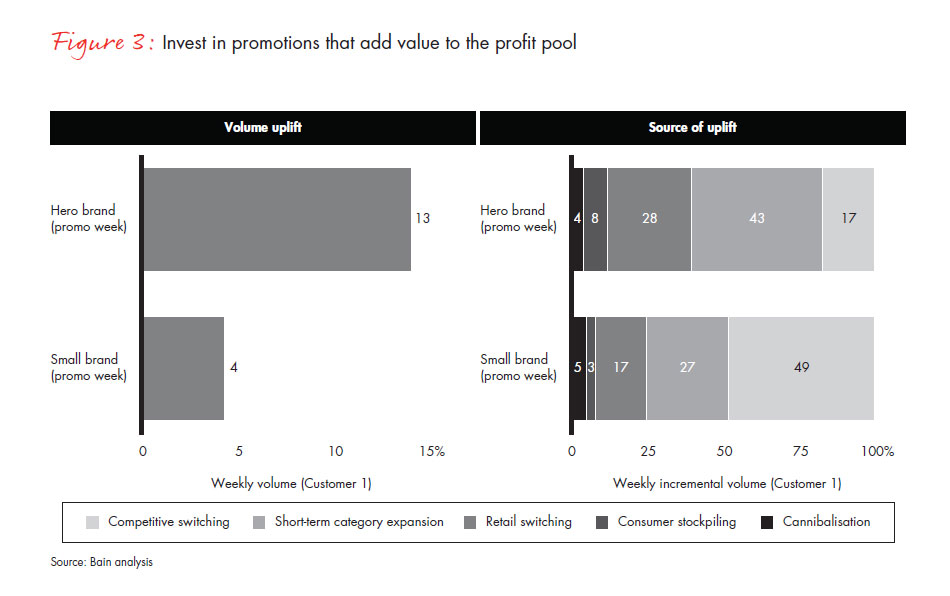

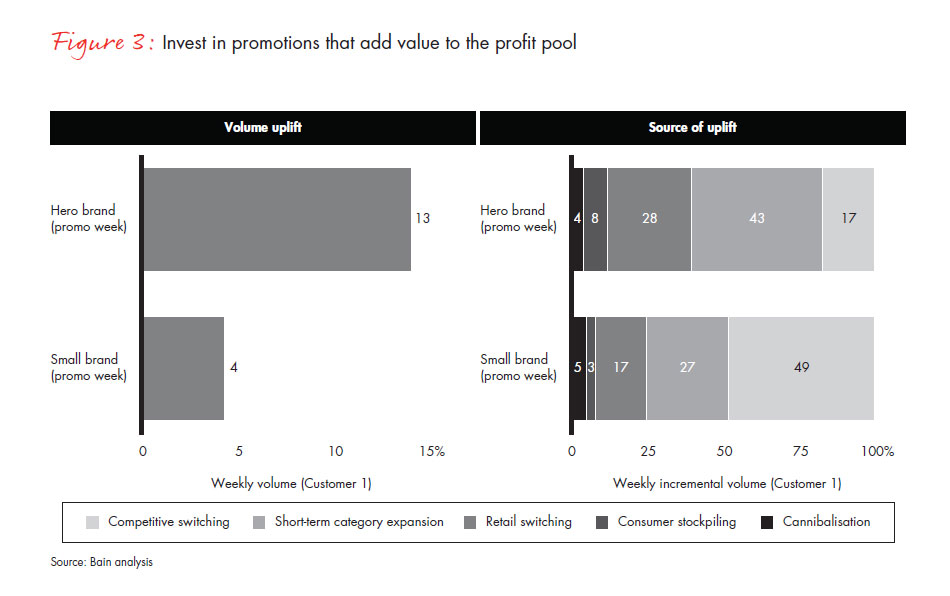

Different studies show that when companies promote “hero” brands instead of small brands, they are more successful in expanding the category in the short term, and thus add value to the profit pool (see Figure 3). For example, in one category, promotions for a hero brand generated three times the volume that promotions did for a small brand—with 43% of the hero brand’s incremental volume coming from short-term category expansion, compared with 27% for the small brand. Nearly half of the incremental volume from the small-brand promotion came from competitive switching (compared with 17% for the hero brand). Promotions that encourage competitive switching generally do not increase the profit pool.

Leaders view promotions as one of many levers to attract shoppers. Some companies excel at the mechanics of promotions. Others focus on creating new shopper occasions. Still other companies capitalise on shoppers’ willingness to pay more. They’re skilled at adding value to a category and exciting customers. In categories where it’s possible, they encourage trade-ups to premium versions. Shoppers need a reason to trade up—any visual cue that what they’re purchasing is more premium than usual. That’s why some companies offer specialoccasion packaging, such as seasonal gift packs, for an additional cost. For example, customers pay more for Lindt’s chocolate in the shape of a Santa or its iconic gold bunny. Switzerland’s Lindt & Sprüngli moved away from the traditional view of the chocolate category—as one defined by tablets and bars—to one that relied on such occasions as gifting and such behaviours as impulse shopping.

Other consumer goods players take a different approach to getting consumers to trade up: an exceptional in-store experience with a unique cache. Few companies illustrate this as successfully as UK’s Hotel Chocolat. The store’s boutique design showcases its artisan products with creative displays while tastings and experts encourage shoppers to become chocolate connoisseurs.

In addition to promotions, there’s the issue of pricing: Winning companies invest in pricing strategies alongside their promotion strategies. Many others still use simplistic models for price elasticity, failing to position prices strategically relative to the right benchmark products. But leaders rigorously research the options: For example, understanding that a shopper in a convenience store may opt for a higher-priced bottle of a soft drink if a can is unavailable—and then striving to ensure the right products are in the right packs in each channel.

The bottom line: While the UK environment for sellers of FMCG may feel uninspiring, there are exciting ways to go after the headroom for growth. With grocery retailing now stabilising, brands can take a fresh look at their strategy for growing and profiting in the years ahead.

Start by learning how shoppers really make purchase decisions—as opposed to how you think they do. Make the most of the new fact of life that shoppers are demonstrating less and less exclusive brand loyalty. Invest to introduce novel occasions for shoppers to use your products and to win them over in the store. Use promotions strategically. As a handful of outperforming companies are discovering, these are the new rules for changing— and thriving—with UK shoppers.

Richard Webster is a partner in Bain’s London office and a member of the firm’s Consumer Products and Retail practices.

Sanjay Dhiri is a partner in Bain’s London office and a member of the firm’s Consumer Products and Retail practices.

Tory Frame is a partner in Bain’s London office and a member of the firm’s Consumer Products and Retail practices.

Phil Dorsett is a director at Kantar Worldpanel.

This work is based on secondary market research, analysis of financial information available or provided to Bain & Company and a range of interviews with industry participants. Bain & Company has not independently verified any such information provided or available to Bain and makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, that such information is accurate or complete. Projected market and financial information, analyses and conclusions contained herein are based on the information described above and on Bain & Company’s judgment, and should not be construed as definitive forecasts or guarantees of future performance or results. The information and analysis herein does not constitute advice of any kind, is not intended to be used for investment purposes, and neither Bain & Company nor any of its subsidiaries or their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees or agents accept any responsibility or liability with respect to the use of or reliance on any information or analysis contained in this document. This work is copyright Bain & Company and may not be published, transmitted, broadcast, copied, reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without the explicit written permission of Bain & Company.